Paradiso Festival 2015: Two Confirmed Deaths & Ten Arrests

A 22 year old Portland man and a 22 year old Canadian man passed away after attending Paradiso 2015. The cause of death has not yet been released in either case, but multiple news outlets are reporting that a combination of heat and drug use may have played a factor. Both of the deceased were found unresponsive at the event then later passed away at regional hospitals. 53 patients were treated in Quincy this year, with 8 being transported to Seattle. 10 people were arrested.

2015’s Paradiso death brings the total deaths of attendees at events put on by USC Events to two three this year so far, one of which occurred at Life in Color Seatac 2015. With Freaknight being shut down early last year, we wonder what USC Events has in store for the future…

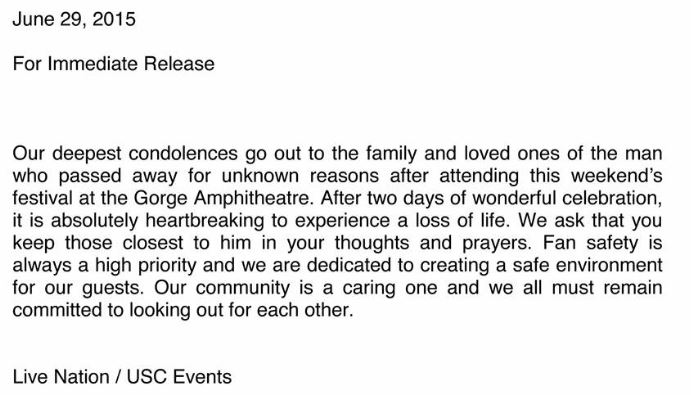

Live Nation, the co-owner of USC Events, and USC Events released the following official statement via Facebook on 6/30/2015:

Live Nation appears to be taking a tough stance against drug use at their events. Live Nation formerly allowed harm reduction efforts such as DanceSafe and the BunkPolice to assist with drug testing on site at events, however this year at Bonnaroo Live Nation banned such services – YourEDM reports: “Bonnaroo Shuts Down The Bunk Police and Confiscates Hundreds of Drug Kits“. Additionally, DanceSafe was recently removed from Electric Forest. Note that one person died this year after attending EDC Las Vegas, which also experienced record high temperatures.

Our condolences go out to the friends and family of the deceased. No event or drug is worth losing a life for. We would like to reiterate our stance on harm reduction at events and drug testing: Harm reduction services at events can save lives and test your drugs: PMMA/PMA is making the rounds again and also in the Pacific North West there have been multiple reports of methamphetamine or other stimulants being sold as Ecstasy. No life is worth risking over questionable drugs, and no life lost is worth a reduction to legal liability by the event promoters/producers. Lightning in a Bottle (the DoLab) in California has successfully integrated harm reduction services at their events in a way that is beneficial for all.

If you disagree with the way that Live Nation/USC Events or other large EDM event companies have been approaching harm reduction at their events, sign this online petition today: Amend the RAVE Act.

The Spokesman Review reports: “Paradiso music fest fan dies in hospital”:

The Paradiso electronic music festival in Central Washington turned deadly for one young man and sent dozens more to area hospitals for heat- and drug-related illnesses, officials said. A 22-year-old Portland, Oregon, man died Sunday morning after attending Paradiso at the Gorge Amphitheater in Central Washington. Beau B. Brooks died at Confluence Health-Central Washington Hospital in Wenatchee.

A cause of death has not been released, but it may be related to drug use or the heat, said Kyle Foreman, spokesman for the Grant County Sheriff’s Office. Saturday’s high in nearby Quincy was 105 degrees.

The sheriff’s office is investigating the death, which comes two years after a 21-year-old Washington State University student died at Paradiso from dehydration caused by the heat and methamphetamine intoxication. “I want the victim’s family to know how sorry I am for their loss, and to know that I have committed a major crimes detective to investigate and find out what happened,” Grant County Sheriff Tom Jones said. Many more of the festival’s young fans took ill and were treated at the concert venue or rushed to hospitals in Quincy, Wenatchee and Seattle.

Quincy Valley Medical Center treated 53 patients from Paradiso over the weekend. That’s slightly more than last year, said Alicia Shields, the chief nursing officer. “The combination of high heat and multi-substance abuse resulted in a significant number of life-threatening conditions,” Shields said. Eight patients were admitted to the hospital for further evaluation and treatment, and eight were transferred to Confluence Health or Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Crowd Rx, the company that the Gorge contracted with to provide on-site medical services, treated more stable patients so Quincy Valley medical staff could focus on critically ill patients, Shields said.

Festival promoter Live Nation Entertainment did not respond to requests for comment today. The two-day music festival drew 27,500 fans to the outdoor concert venue near George, Washington. The sheriff’s office said it had 74 calls for service related to Paradiso and booked 10 people into jail. Crimes included assaults, drug possession, theft, attempting to elude, trespassing, vehicle prowl, and hit and run. Starting last year, more water stations were added for the two-day concert, and the event promoter began contracting with AMR to have medical personnel and ambulances at the venue.

Update: KPTV Portland reports that the deceased separated from friends and disappeared into the crowd. He was discovered unresponsive several hours later with his internal body temperature reaching 110 degrees.

Second Death – the Spokesman Review reports: “2nd Paradiso festival-goer dies in hospital“:

A second man has died after becoming ill at the Paradiso Music Festival in Central Washington, the British Columbia Coroners Service confirmed Monday. Vivek Pandher died Saturday in Vancouver General Hospital in British Columbia. The 22-year-old was one of dozens who were rushed to emergency rooms after attending the festival last week at the Gorge Amphitheatre.

Barb McLintock, a spokeswoman for the Coroners Service, said Pandher was found unresponsive at the festival. He was initially treated at Quincy Valley Medical Center, then transferred to Confluence Health in Wenatchee, said Kyle Foreman, a spokesman for the Grant County Sheriff’s Office. The cause of Pandher’s death has not been determined. Many who were treated after attending the festival suffered drug intoxication or heat exhaustion.

Update: KPTV Portland reports that the deceased separated from friends and disappeared into the crowd. He was discovered unresponsive several hours later with his internal body temperature reaching 110 degrees.

Overdose deaths at American music festivals are becoming about as common as mass shootings in America. When will the people in charge learn? Harm reduction groups like dance safe would be a godsend at USC events. Seems like an easy answer

I wonder how many of today’s young ravers would throw away their “molly” at an event even if it was found to be something other than MDMA? Sadly I feel like most would continue to consume rather than enjoy the show sober and responsibly. Maybe I’m jumping to conclusions, but it seems the scene promotes “turning up” and “raging” more than living to dance another night.

It is important to note that people who die of overdose at these events THINK they are taking MDMA. If the war on drugs (i.e. waste of billions of dollars) had not made a mostly innocuous drug so hard to come by would we see so many overdoses from bath salts and meth? I don’t think so. Just another example of how trying to control people’s behavior when they don’t want to be controlled can backfire. I am an advocate for decriminalization, taxation and quality control… And I don’t even use molly at festivals because dancing is my drug!

JUST SAY NO: Do zero-tolerance drug policies at rave festivals actually make the problem worse?

When 22-year-old filmmaker and electrical engineering student Vivek Pandher was found unconscious at the Paradiso Festival at the Gorge Amphitheatre on June 27, he was way too far gone to tell anyone what had happened. Pandher was rushed to the Quincy Medical Center by ambulance, his temperature critically high.

At the hospital, crisis mode was already in effect. Employees had been brushing up on their party-drug knowledge all year in preparation for the festival, and as temperatures climbed in the days leading up to Paradiso, the three-bed emergency room had tripled its staff to get ready for the deluge of dehydrated concertgoers. Pandher was one of 53 of them hospitalized during the festival, which was attended by 27,500 people on a weekend when temperatures reached 105 degrees.

Like Pandher, many patients arrived catatonic, their body temperatures critically high. “We saw illegal drugs, lots of impure molly, and it makes diagnosis and treatment more of a challenge,” says Quincy Medical Center’s Glenda Bishop. Pandher’s heart had stopped and he was flown to a British Columbia hospital by helicopter. It would be too late. Deprived of oxygen, his brain had checked out. He would become the second casualty of this year’s festival. “The hospital told us he got heat stroke,” says his younger sister Kirad Pandher.

Pandher’s tragic death isn’t an isolated incident. Young people have dying at electronic dance music (EDM) festivals like United State of Consciousness (USC) Events’ Paradiso around the region and nation at alarming rates in recent years. “When people get in trouble with MDMA, they raise their heart rate so high that they basically sort of burn up,” says Tammy Anderson, a University of Delaware professor who studies rave culture. A 24-year-old man died at the Electric Daisy Carnival in Las Vegas last month; a 20-year-old man died at USC’s Life in Color paint party in Tacoma in May; a 20-year-old man died at USC’s FreakNight party in Seattle in October; a 23-year-old woman died at the Safe in Sound Festival in Boise in October. Toxicology information isn’t available in Pandher’s case yet, says Barb McLintock at the BC Coroners Service. Anderson says no one knows how many of these deaths have occurred nationally, but numbers from the Drug Abuse Warning Network show emergency room visits for MDMA climbed from 10,227 in 2004 to 21,836 in 2010.

Rave culture arrived in the U.S. in the 1990s. Back then, promoters at underground raves embraced the drug culture, and harm-reduction services like drug testing were the norm at events. Concern about drug use at raves reached a fever pitch in 1998 after 17-year-old Jillian Kirkland overdosed on ecstasy at a rave in New Orleans, and in 2003 Congress passed the Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy (RAVE) Act. Now known as the Illicit Drugs Anti-Proliferation Act of 2003, the law made it possible for the federal government to prosecute promoters for drug use at their events, slapping them with fines to the tune of $250,000 and up to 20 years in prison. The law worked to shut down underground raves. But instead of disappearing, the culture moved out of abandoned warehouses and into the mainstream; today the Association for Electronic Music values the industry at $6.2 billion.

Promoters implemented zero tolerance policies to avoid running afoul of the RAVE Act. The drugs didn’t go away, though. “The rub with that is that rave culture always had drug culture worked into its fundamental fabric,” says Anderson. “Who can stay up and dance until 6 am without being on drugs?”

Industry insiders don’t see it that way.

“The electronic dance music industry does not have a drug problem,” says Edwin Reyes, USC’s health and safety director. “I do rock concerts that have the same amount of drugs.” Reyes says there’s only so much that USC can do to make their events safe. He’s added extra staff and free water stations, and he’s been promoting a message of abstinence and personal responsibility for years. “Ultimately it’s personal responsibility what you do; if you want to use drugs and you do all of them in line because you don’t want to get busted, that’s on you,” says Reyes.

Anderson says she worries that promoters are hiding behind the RAVE Act and using it as an excuse to not offer better medical care and drug prevention education at their events.

“The RAVE Act may have been well-intended, but it has ended up killing people,” says Inge Fryklund of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a group of former law enforcement officers who advocate for legalizing drugs. “We’ve decreed the death penalty for people who are young and not too careful about who gives them what.”

As raves went mainstream, harm-reduction groups that attend events to offer drug-adulterant testing services and brochures with warnings about bad drugs headed underground. If the Bunk Police — a drug-test kit vendor — want to offer harm-reduction services at festivals, founder Adam Auctor has to smuggle in the baseball-sized kits. Many promoters turn a blind eye, but not USC or Live Nation (the company that manages the Gorge), Auctor says. “They don’t understand harm reduction,” he says. “They prefer to decrease liability by removing us and treating us like criminals.”

Live Nation did not respond to requests for comment.

Reyes says that allowing drug-test purveyors like the Bunk Police or DanceSafe — a harm-reduction group that tests drugs for adulterants at events and hands out educational materials — would essentially be condoning drug use. “Drug use is prohibited at our shows,” says Reyes. “To set up drug testing is to say it’s OK to come with your drugs as long as they’re good drugs.”

Quincy Medical Center’s Bishop says Paradiso’s organizers need to do more, and that the patients who arrive from the festival are in far more critical condition than those who arrive during other Gorge events. “Something needs to be done,” says Bishop. “Three deaths in 24 months is three too many.”

After Dede Goldsmith’s 19-year-old daughter died of MDMA-induced heat stroke at an EDM show in 2013, she started a petition to amend the RAVE Act and allow harm reduction back into the rave scene. But Anderson says amending the Act won’t happen quickly.

“It will require a federal response by Congress or the president. I don’t see it on the agendas any time soon,” says Anderson. “The feds aren’t talking about ecstasy.”

Pandher’s family are left to wait for the toxicology report and cope with their loss.

“When we got here from India and went to the hospital and got to know he was no more, that he was brain-dead, the doctor told us that he came … and donated all his organs. My father heard that and he clapped, and we felt better after hearing that,” says Kirad Pandher. “He lived his life completely and was very happy.”

Rolling Stone reports: “Meet the People Who Want to Make It Safer to Take Drugs at Festivals“:

Pasquale Rotella Responds to Recent Criticisms of Dance Music Culture:

Tacoma News Tribune reports “13 taken to hospital during Tacoma FreakNight event“:

Roughly a dozen people went to the hospital Friday and Saturday evenings during the FreakNight electronic dance show at the Tacoma Dome.

Tacoma Fire evaluated 107 patients Saturday night, nine of whom were taken to the hospital, spokesman Joe Meinecke said.

“Alcohol or possibly drug use seemed to have contributed to the majority of those transports,” he said.

Crews took seven to the hospital in stable condition, and the other two were in more serious condition.

Four went to the hospital Friday night: two in serious condition.

Meinecke declined to say whether any of the injuries were life-threatening, due to federal privacy laws, but the Pierce County Medical Examiner’s Office said Sunday that none of the 13 taken to the hospital had died.

“Our report from our security and safety teams says the event went really well,” said Alex Fryer, spokesman for promoter USC Events. “I think it was a really good show all the way around.”

They increased safety measures this year. The second night of the electronic dance show was canceled in 2014 at the WaMu Theater in Seattle after a 20-year-old man died from overdosing on Molly, a type of ecstasy. Hospital transport was required for 16 others.

The company should decide in the next couple months where next year’s FreakNight will be, Fryer said.

Pingback: Paradise Or A Recipe for Disaster? | wintersspencer

VICE/THUMP reports “How Do We Stop Drug Deaths At Festivals?“:

When Ashton Soete couldn’t get in touch with his friend Shane Zimmardi who he’d arranged to meet up with at the Life in Color Festival in Tacoma, Washington in May 2015, he didn’t think too much of it, assuming Zimmardi just didn’t have his phone on him. The next day, he got a call from Zimmardi’s brother, Forrest, who told him Zimmardi was in the intensive care unit at a local hospital. In the early hours of that morning, Zimmardi had been found passed out underneath some bleachers on the festival grounds after taking MDMA—at least, that’s what he’d intended to take.

While Zimmardi was lying in the hospital ward, breathing through a machine with tubes snaking through him, Soete tried to piece together what happened. Zimmardi had gone to the festival with his brother and some other friends, he took some drugs, then around 10PM he told Forrest he’d be right back. His brother and the rest of his group didn’t see or hear from him again; at around 4AM, he was found by another festivalgoer under the bleachers.

Soete later learned the person who found Zimmardi was an off-duty member of a nonprofit called Conscious Crew, who roam festivals looking out for people in trouble. Several more members of Conscious Crew were with Zimmardi when the medical team decided to call an ambulance, and they waited with him until it arrived.

“The Conscious Crew staff provided [Zimmardi] with a safe place up until his transport,” Soete said. “I would hate to imagine what would have happened if he was never brought to them; perhaps we wouldn’t have had the few days that we did to say our goodbyes.”

On May 13, 2015, after four days of assisted breathing, the decision was made to switch off Zimmardi’s life support. He was 20-years-old. Four months after his friend’s passing, Soete signed up as a volunteer with Conscious Crew.

When someone dies after taking drugs at a music festival, the press and public’s attention tends to hone in on the fact they took an illicit substance. A number of widely-publicized deaths at EDM festivals in the last few years has sparked a fierce debate centered on how to stop young people from doing drugs, that swings from blaming legislation like the RAVE Act, to demonizing rave culture for its alleged encouragement of drug taking. In the past a knee-jerk impulse to act quickly against drug use, couched within a prohibitionist attitude towards substance abuse, has resulted in government policies written from a criminal justice perspective that punish drug users and event organizers—or try to stop raves altogether.

The legislation thought of as having done the most damage when it comes to drug safety at festivals is then-Senator Joe Biden’s The Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy Act, passed by Congress in 2003. Renamed the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act, it’s still commonly known as the RAVE Act. The legislation allows authorities to prosecute event organizers and venue owners for facilitating the use or distribution of controlled substances on their premises. The RAVE Act has been criticized by the parents of kids who’ve died at raves for being counter-productive because many promoters stopped providing things like cool down rooms and free water, fearing it would send an image of encouraging drug use.

America needs a drastic shift in the way the country thinks and talks about drugs—accepting that people are going to do them no matter what punitive system is in place, and taking a non-judgmental approach to minimizing risk. In recent months, grassroots groups and policy reform advocates have made significant strides to accomplish this paradigm shift in drug policy from abstinence to harm reduction. And in the electronic music community, the change is felt most acutely in field of harm reduction at festivals.

On March 22, LA is expected to sign into law a forward-thinking set of health and safety requirements for events of 10,000 or more attendees on county property. Seattle’s city officials are also taking a hands-on approach to reducing fatalities at festivals, holding summits in recent months to come up with safety suggestions for promoters and patrons. These initiatives are a small—but significant—step towards finding ways to curb drug deaths at festivals that actually work.

The 55 health and safety recommendations that will soon regulate festivals (and other large-scale events) in LA county come on the heels of the drug-related deaths of two teenage women at HARD Summer in Pomona, California in 2015. Following those deaths, LA County Supervisor Hilda Solis called for a temporary ban on raves on county property until a full investigation had taken place, which resulted in the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors (LA’s governing body) convening an Electronic Music Task Force with the directive of making festivals safer for all patrons. Comprised of city officials and law enforcement officers working with groups in the dance music community that promote safe experiences, the current task force is a reincarnation of a similar group that formed in 2010 when 15-year-old Sasha Rodriguez died of drug-related causes at Electric Daisy Carnival in LA.

The regulations include limiting events to people over 18; incorporating a cool down period after last call on booze that gives people time to sober up; placing amnesty boxes at the entrance for people to voluntarily give up their substances; and requiring organizers to provide educational material on the dangers of alcohol and drug use. If event organizers do not meet the requirements, the county will have the authority to shut the event down.

This new legislation has been largely welcomed by advocates of harm reduction for being based on scientific evidence and for encompassing a wide range of stakeholders’ interests. Although the set of regulations is only at county-level within one state, the hope is that it provides a template for other states to follow.

Missi Wooldridge, the director of DanceSafe—a Denver-based nonprofit advocating for health and safety within the electronic music community—told THUMP that she was pleased the task force in LA came up with a list of recommendations instead of completely banning raves.

“Banning EDM events won’t stop drug use,” said Wooldridge, who was part of the wider team of experts consulted with by the task force. “It will only make drug-taking more risky by pushing it into the underground.”

However, some harm reduction advocates criticized the legislation’s requirement that festivals have to employ undercover cops and sniffer dogs, worrying that this will cause ravers to dangerously pre-load before coming into an event. Morgan Humphrey, of the New York-based drug policy reform nonprofit Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) said: “The use of drug sniffing dogs often causes medical emergencies when people who see the dogs take all their substances at once.”

Stefanie Jones, Director of Audience Development at the DPA wrote a blogpost on the recommendations that praised the task force for how far they’d come in writing a “strong plan to reduce deaths and hospitalizations,” but cautioned that promoters may still find that venues don’t want to host their electronic music events.

Elsewhere on the West Coast, in Seattle—where the promoter behind the Life in Color festival where Zimmardi died is based—the city has been championing a progressive approach to festival safety via an annual Music Safety Summit now in its third year.

Hosted by the city’s Office of Film and Music, and attended by harm reduction experts and members of the rave community, the summit resulted in a list of takeaways for festival promoters and attendees to follow. They included making patrons aware of the Good Samaritan Laws in Washington that protect anyone seeking medical attention for drug emergencies from prosecution, and encouraging people that if they do decide to take something, to start with one dose.

Kate Becker, the director of the Office of Film and Music in Seattle, oversees all aspects of nightlife in the city. She said the Music Safety Summit is a crucial forum for promoters and officials to work together. Becker also spoke against a “prohibitionist mindset” that’s often used when talking about drug use at festivals, pointing out the hypocrisy of those who are “ok with what happens with alcohol at a football game, but not ok with something they’re not familiar with that’s impacting young people.”

Helping the public separate truth from misconception is something that organizations like Drug Policy Alliance and DanceSafe have long championed. The lack of education around drug use is of particular concern at festivals, where external factors—such as high temperatures, sleep deprivation, not eating much food, and dehydration—will impact drug-taking in ways users might not realize.

“When it comes to MDMA, the term ‘overdose’ is often not even applicable,” Jones from the DPA said. “The most common cause of death related to MDMA is actually heatstroke.”

DanceSafe’s Wooldridge sees festivals as a valuable platform for educating ravers so they can make informed choices: “From a public health perspective,” she asked, “where else can we get 20,000 to 100,000 young people all in one place, with messaging and services in place to really educate around drug use?” Thus, DanceSafe has booths set up at a handful of festivals, where volunteers give out informational flyers and answer questions from attendees.

Balanced, evidence-based information—as opposed to scaremongering or focusing on criminal penalties—on drug use is difficult to find. Perhaps the most comprehensive US-based resource is the Erowid website—a user-driven database set up by a couple from California 20 years ago of over 350 psychoactive drugs. DanceSafe also provides information on its website for drugs associated with raving: MDMA, psychedelics, stimulants, and marijuana. However, there is no official government database that people can turn to for scientific and legal information on illicit substances.

The lack of fact-based information around drug use is exacerbated by the reluctance of American festivals to allow on-site drug testing. Widely adopted at festivals in Europe where harm reduction is considered to be more advanced, drug-testing isn’t common at US festivals.

Some US-based festivals have barred harm-reduction organizations from providing drug testing services. Explaining why DanceSafe is currently not allowed at his events such as Electric Daisy Carnival, Insomniac Events CEO Pasquele Rotella wrote on his Reddit AMA: “Unfortunately some people view partnering with DanceSafe as endorsing drug use rather than keeping people safe, and that can prevent producers from getting locations and organizing events.”

Wooldridge estimated that DanceSafe tests drugs at fewer than 10 festivals in the States, which Backwoods Music Festival as one of the few exceptions.

“People get very squeamish talking about [drug education],” said the DPA’s Jones. “But if you have someone who is determined to take this substance, would you rather tell them the safe recreational dose versus, ‘well, just don’t do it?’ And then, they’re going to go off and do something ignorant? That’s where the problem is.”

The main reason why many US festivals don’t provide services like drug testing, crisis tents, or in some cases free water, has to do with legislation

Jones added that there’s also no guarantee that when users think they’re taking molly, they’re actually getting MDMA. While pill-testing is hotly debated, there is anecdotal evidence that the services help ravers make better choices.

The gold standard of harm reduction at festivals in North America is Shambhala Music Festival in British Columbia, Canada, where pill testing has been in effect for 16 years. Stacey Lock, Shambhala’s harm reduction director, said she’s found ravers will ditch their baggies if they find out a drug is not what they thought it was. Lock said the festival has seen the rates of drug-related incidents go down significantly over the years. “When we greet everybody at the gate, we tell them where the health and wellbeing zone is, and remind them that you can always dose up but not dose down,” she said. “By providing these services, there have been way less incidents.”

Being in Canada and so free from the constraints of the RAVE Act, the long-running festival has a dedicated harm reduction department, which, in addition to pill testing, provides a crisis tent for people to chill out in if they get too high; volunteers who wander the festival to help out people in distress; and special lodgings for sober ravers. In addition to drug and alcohol safety measures, the festival also provides harm reduction services for female attendees, as well as sexual health services.

Lock believes the outreach program has worked because of its friendly, welcoming approach. “It’s not like a security-enforced atmosphere, but instead that we care about you and want you to make good choices,” she said.

Joseph Pred, founder of MARS an emergency services company that has worked with hundreds of US festivals, also wants to see festivalgoers make better-informed choices. Over the 16 years the former Burning Man Chief of Public Safety has provided emergency medicine at festivals, he’s seen a lot of misinformation among ravers. “People who go to festivals, particularly those with a younger demographic, think they will get in trouble with law enforcement for seeking medical treatment for being high,” he said.

Pred said when it comes to preventing medical emergencies at festivals, it’s vital that everyone involved in the event—from patrons and festival organizers, to community leaders and law enforcement—participate in the health and safety effort. “The truth is that this is a social issue and everybody plays a part,” he said. “Harm reduction is the same thing—everybody has a part to play.”

The principal reason why many US festivals don’t provide services like drug testing, crisis tents, or in some cases free water, has a lot to do with legislation. The advocates THUMP spoke to all said they find many organizers are hesitant to adopt progressive harm reduction measures on-site because they’re concerned they will face legal or financial consequences related to the RAVE Act.

“The festivals are often scared that if they include education or harm reduction services, it acknowledges that there’s going to be drugs on-site. They get very nervous about it,” Jones said. However, Cameron Bowman, a legal expert on the RAVE Act, told THUMP that he doesn’t know of any cases in which a prosecution was actually brought forward against a festival. “I often call the RAVE Act the ‘Keyser Soze’ of laws,” he said. “Everyone is afraid of it, but no one can recall anytime it was actually used.”

Regardless of whether the threat of the RAVE Act is real or imagined, it’s one of the reasons why harm reduction at US festivals is in the dire position it finds itself today. But between the new legislation in LA and the safety measures in Seattle, policy is slowly catching up with society’s outlook on drug safety, which is shifting from abstinence to harm reduction.

For Soete, as he processed everything that surrounded his childhood friend’s death at the Tacoma festival, he realized that Zimmardi’s story embodies the reasons why this change needs to happen. “Shane wasn’t educated on the drugs that are out there, but that’s because there’s no one providing this education other than the internet,” he said. Soete is very welcoming of the movements on a policy front, but he cautioned that people don’t need to hold out for the bureaucratic cogs to turn to make a difference this festival season.

“People don’t need to wait until laws are passed to get educated, and to educate their friends,” he said. “That one little piece of information that you might spread on to your friends could save their lives. It might make the difference between them coming home with you that night or ending up in the hospital.”